In the narrow, white-water sliced opening of the Panjshir valley, a verdant bastion protected by barren mountain walls, Mas‘ud’s troops halted the Taliban by blowing the cliffs down upon their Taliban enemies. He survived the Soviets and, in the summer of 1997, this most renowned of the mujahidin’s generals surprised the world once again. intelligence analysts had often anticipated Mas‘ud’s defeat by the Red Army, but that did not happen. Except one: Mas‘ud, whom the writer Robert Kaplan has rightly described as one of the great guerrilla leaders of the twentieth century, perhaps the equal to Giap or Mao.

By 1997, they had conquered 90 percent of Afghanistan and all the great resistance commanders of the Soviet-Afghan war. The Taliban are primarily Pashtuns (known in Rudyard Kipling’s day as the "Pathans"), the dominant tribesman of southern Afghanistan and Pakistan’s northwest frontier. The Taliban first rose up in 1994 among the Soviet-Afghan war’s forgotten children -the poorly-educated young men of the refugee camps and shattered villages of the Pakistani-Afghan border. But without this helicopter and others like it, most of my companions would now probably be dead or in exile, victims of the Taliban Islamist religious movement. The helicopter we were riding in-a leftover from the Soviet–Afghan war-was quite possibly once used by the Red Army to kill the older brothers and fathers of my traveling companions. Looking at a dozen men, most dressed in baggy cotton pants and safari vests, sitting and sprawled on ammunition and grenade boxes, foodstuffs, money bags, unmarked white-plastic liquid bottles, and racks of soda-pop cans, I pondered the irony. I tried to forget the words of an Iranian friend in the United Nations who told me that Mas'ud's helicopters crashed regularly from mechanical difficulties and anti-aircraft fire. This was a mechanically simple machine to maintain, I reassured myself, as I slid down the bench, allowing a bearded, brown-toothed ox of a man to swing his hips and AK-47 assault rifle into my place. Two of them across from me were vibrating. Rising higher toward the mountain passes that would take us from Tajikistan into northern Afghanistan, I focused on the bolts holding the chopper together.

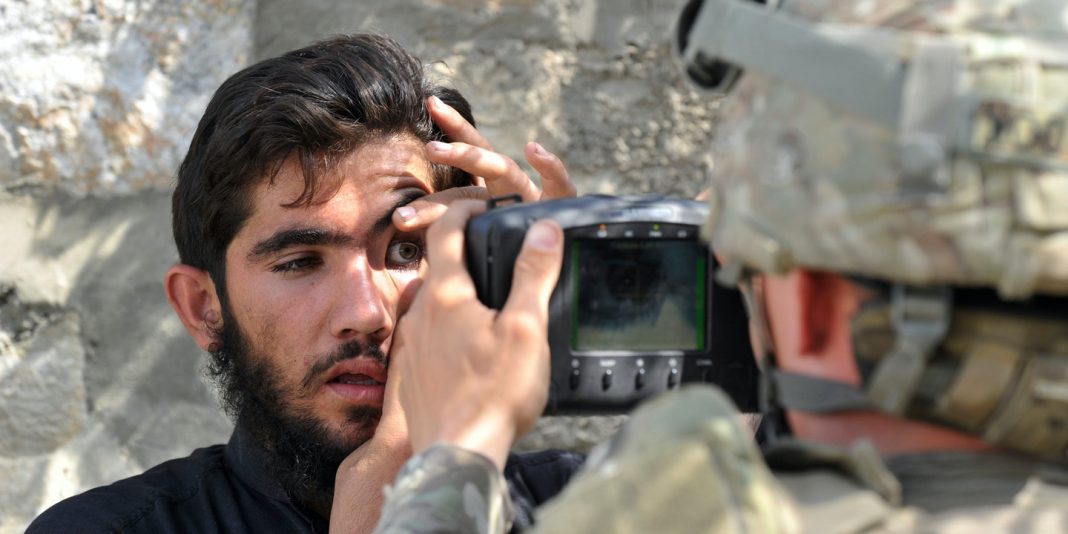

#TALIBAN HIIDE AFGHANSINTERCEPT SKIN#

The banter of the young Afghan soldiers, cut briefly by a quick prayer, disappeared in the engine’s roar and the squeals of the stressed skin of the thirty-year-old helicopter. They, alone among Afghanistan’s many ethnicities and tribes, have successfully resisted the Taliban juggernaut that had conquered most of the country by late 1996.Īs the Soviet-made MI–8 helicopter lifted off the grass field on the outskirts of Dushanbe below the burnished foothills of the Hindu Kush, I stopped thinking about Usama bin Ladin.

I was on my way to see Ahmad Shah Mas‘ud, whom I'd watched from a distance when I was in the Central Intelligence Agency, and his mostly Persian-speaking, ethnically Tajik, Afghan forces. Moscow’s fear of Islamic radicalism in Afghanistan had turned enemies into friends. Russian soldiers, who still control that country’s borders, had checked my visas and warmly slapped some of the Afghans on their backs. My trip began in the ex-Soviet Republic of Tajikistan. I wanted to talk to Mas‘ud’s front-line soldiers who had fought the Taliban and their Arab auxiliaries, as well as to the prisoners of war Mas‘ud had collected. My goal was to visit Ahmad Shah Mas‘ud, the military commander of northeastern Afghanistan, travel to the front line between him and the Taliban, and if possible, reach the outskirts of the Taliban and Islamist Arab training camps north of Kabul. Given the impasse of going through the south, I tried the somewhat novel idea of approaching Usama bin Ladin’s training camps from the north. From there, they try to gain access into southern Afghanistan where they inevitably confront the tight-knit Taliban and Islamist Arab circles which surround America’s most-wanted terrorist. Most journalists and American officials who want to see what Usama bin Ladin is doing make trips that begin in Islamabad, Pakistan, and then go to the gateway city of Peshawar.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)